How Flood-Proof is Berlin?

The city is famously built on swampy land at the confluence of multiple rivers. But its geography is actually key to its protection

Watching news reports of the devastating floods in the southeastern United States and in Valencia, Spain made me wonder about our risk level here.

I would have expected mountain communities in western North Carolina—where I have several friends and family members—to be the last place affected by hurricane-spawned flooding.

We live in a ground floor apartment in Berlin, a city built on a swamp at the confluence of two large rivers and known for its flat terrain and high water table. What is our risk if a severe weather event were to dump a year’s worth of rain in a day—the way that it happened in Spain?

My research turned up some surprising answers.

Historically, experts say Berlin has not had a problem with flooding thanks to a number of geographic factors.

In 2021, Andreas Friedrich, a meteorologist with the German Weather Service, told the online news magazine B.Z. that the flat landscape, sandy soil, and the presence of several slow-moving streams and large lakes combine to allow better absorption of excess rainwater.

“That is not the case in western Germany,” Friedrich said, responding to questions about the flooding along the Rhine that year. “There, the soils become [quickly] saturated. In addition, there are narrow valleys and innocuous little rivers that are not able to absorb the water quickly. This is how a small stream becomes a raging river with a tidal wave of up to one meter.”

Storms in North Rhine-Westphalia dumped around 200 liters of rain per square meter in one week in July of 2021, resulting in flash floods that killed 135 people and destroyed homes and businesses. But a similar amount of rain fell that June in Uckermark, about 100 kilometers north of Berlin, with relatively little damage.

“There were some flooded cellars, but that was about it,” Friedrich noted.

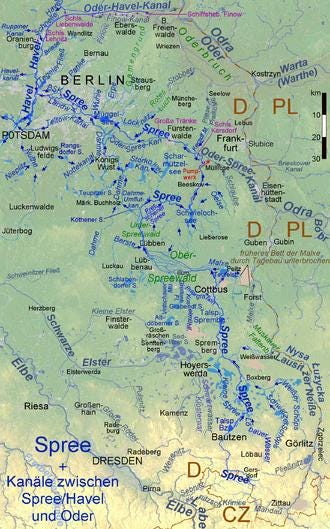

There are higher-risk areas along the Tegeler, Panke, Erpe Rivers and the Lower Spree and Lower Havel riverfronts. These areas are listed on the flood maps maintained by the Berlin government as areas of high flooding probability, expected to see flooding events more often than once every 100 years.

Room to drain

Protected or restored wetlands and wide, meandering rivers allow excess water to spread out over a large area, instead of being concentrated in smaller channels or bodies of water that are quickly overwhelmed, writes Sonja Jähnig with the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries.

Jähnig and her colleagues studied several cities and regions in Germany and the United States where initiatives to restore floodplains and natural streambanks reported benefits in the areas of stormwater management, water quality, and habitat restoration.

“Conventional flood control has emphasized structural measures such as levees, reservoirs, and engineered channels—measures that typically simplify river channels and cut them off from their floodplain, both with adverse environmental consequences,” Jähnig explains in the introduction to their findings published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Science.

While structural measures prevent frequent small and medium-scale floods, they also create a false sense of security and encourage more construction in former floodplain areas. This actually increases the risk of more serious flooding during extreme weather events, she adds.

The ‘sponge city?’

In recent years, Berlin and Brandenburg have actually suffered from too little rainfall instead of too much. Since 2018, the region has recorded record high temperatures in the summer and record low rainfall. But many of the measures intended to address Berlin’s issues with drought also provide localized flood protection.

The Berlin Water Works (Berliner Wasserbetrieb) is in the process of constructing large, underground rainwater storage basins to collect water during heavy rain events and then gradually release it when it is needed.

According to a report in DW.com, nine of these facilities have already been completed, including one under the Mauerpark, a popular hangout spot in the district of Prenzlauer Berg, where parts of the Berlin Wall once stood.

"The driving force behind this program was not only resource conservation and drought, but also preventing combined sewer overflows," BWB spokesperson, Astrid Hackenesch-Rump told the news outlet.

When there's heavy rain and Berlin's sewage system is at risk of running over, surplus water is stored in the basins. It's then pumped into a purification plant before being released back into Berlin's canals and rivers once the rain has stopped.

As climate change brings more and more unusual weather events, these basins will be even more important. Information published on the BWB’s website explains it this way:

“Our sewer system is designed for “normal” rainfall. In the event of more infrequent heavy rainfall events, it quickly reaches its capacity limits and runs full. Roads and tunnels are flooded and combined wastewater flows into the bodies of water.

Unfortunately, we cannot simply increase the size of the sewers everywhere. The space underground is limited and such projects are expensive. Moreover, the sewers would then be over-dimensioned and too large for “normal operation”. The wastewater would no flow away as well and odours and rust would occur. Therefore, the surface water has to be handled differently in case of infrequent heavy rainfall events: It must evaporate, percolate or be stored.”

Better warning systems needed

One of the main causes for the high loss of life during the floods in both Valencia and North Carolina was the lack of advance warning that a flash flood was imminent.

Residents in Valencia reported that they received flash flood warnings and orders to evacuate after the water had already reached their location. Many in western North Carolina (in the U.S.) said they did not receive the warning notifications at all.

In contrast, a different heavy rainfall event in central Europe - affecting large parts of Romania, the Czech Republic, Austria and Poland - saw a much lower loss of life due to improved warning systems put in place after flooding in 2002 devastated the region.

Climate scientist from the World Weather Attribution organisation concluded emergency management systems across Europe had been reinforced after severe flooding over the last decades and largely worked well. Despite the higher intensity of the heavy rainfall and larger scale of the floodings, the number of fatalities (± 26) is lower than in earlier floods. In 2002 when flooding affected Germany, Austria, Czechia, Romania, Slovakia and Hungary 232 people died. The number of fatalities is also much lower than in the Western European floods in 2021 when over 200 people lost their lives.

Flash floods are much more dangerous and harder to predict in advance, says Eva Nora Paton, managing director of the Institute of Ecology and Chair of Ecohydrology and Landscape Evaluation at the Technical University of Berlin (TUB).

“There are different types of floods. Firstly, there is classic river flooding that involves a concentration of large amounts of runoff water in rivers. This is mostly the result of heavy, continuous rain falling over a large area for six, ten or twelve hours or even one to three days,” she explained to the TUB Climate Protection online information service. “Then there are flash floods, an extreme type of flooding. Flash floods quickly transform small streams into torrential rain rivers. This occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, mostly in very small catchments covering just a few square kilometers. A great deal of precipitation falls in very short periods of time, ranging from just minutes to a few hours. … The acute danger they pose can only be predicted with a very short period of warning. Flash floods can occur anywhere.”

And even when weather reports accurately predict extremely heavy rain, much of the public simply doesn’t understand the risk or know how to react, she added.

“I have now seen warnings from the German weather service as well as private weather services which had forecast rainfall of up to 150 millimeters on a single day,” she explains. “For a hydrologist this can only mean one thing: the town will be flooded. The people living there probably heard this and thought “Ok. Heavy rain.”

More specific plans need to be made to help people who are particularly vulnerable—residents in senior facilities or children and staff in schools and kindergartens, for example—find escape routes and know when to use them, she said.

Cell phone notifications and apps

Anyone who has a mobile phone registered in Germany is probably familiar with the loud test alarm sound ringing in the middle of the day the government decides to test its advance warning system.

The State of Berlin also uses the MoWAS modular warning system to quickly disseminate warnings of public safety threats across a variety of media.

Both the NINA and KATWARN smartphone apps allow users to receive notifications of emergencies, including weather emergencies. NINA is the official nationwide warning app from the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance.1 NINA also provides weather alerts.

KATWARN is a supplemental warning system. It sends alerts about fires, storms, or other sudden emergencies via SMS, email, or the smartphone app and provides tips on what to do. Warnings are precisely targeted to the postal code zones at risk.

And more community-based resources are on the way, Berlin’s Senate Department for the Interior advises:

In the future, emergency contact points or “lighthouses” will be available in Berlin’s different boroughs. They will open as needed – for example, during a blackout. The main purpose of the lighthouses will be sharing information. They will also be able to provide limited assistance, such as taking emergency calls and forwarding them to responders.

Public warning sirens are still functional, but designated to only be used in the event of an extreme threat to public safety at large. You can read more about what the sirens sound like and what they indicate here.

Have a plan

Wherever you live, there’s a good chance that a changing climate will affect local weather patterns—whether it’s significantly less rain and drought or severe storms and rain in areas that historically have not had this problem.

It’s important to be aware of the potential dangers, stay informed, and have a plan to get to safety in an emergency.

In German, its name is the Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe (BBK).

Read More About It

Technische Universität Berlin: Climate Change in Berlin

TUB Climate Protection: ‘Hydrologists Are Not Prepared for Major Flash Floods‘

Flyway Excavation, Inc.: How Does Wetland Restoration Aid in Flood Control?

European Environment Agency: Restoring Floodplains and Wetlands Offer Value-for-Money Solution to River Flooding

Water News Europe: What Went Wrong During the Floods in Valencia?

Water News Europe: Germany Adopts Groundbreaking National Water Strategy

I didn't realise it hasn't been raining much this year in Germany - here in Ireland our summer was a complete washout!