Sixty-three years ago last week, the government of East Germany (formally the German Democratic Republic) began construction of the Berlin Wall - a hard border between the two sides of the city.

It starts with coils of barbed wire and fencing erected overnight between August 12 - 13, 1961, evolving into a permanent concrete wall, 12 feet high. Over time, the East German government would bulldoze a section of land - several meters wide-on its side of the border, relocating all residents and leaving a bare strip of dirt and gravel, and erected a parallel inner wall.

The final Berlin Wall was actually these two walls, with a “death strip” lined with ditches, mines and trip wires in between, guarded by armed soldiers in watchtowers.

It stood for a total of 28 years, separating the democratic exclave of West Berlin from the surrounding East German territory.

Growing up in the United States during the Cold War, my childhood was shaped by the image of two Germanies and this divided city.

Movies, books, and television depicted caricatures of a gray, brutal, totalitarian society absent of all joy and creative expression that was our privilege to experience in the free West.

“Communists” were the shadowy bogeymen of my childhood. We were taught to “appreciate our freedom” lest we end up suffering like them behind the Iron Curtain.

I was 17 years old when the wall ‘fell’ in 1989.

I remember watching images on the news of people celebrating, climbing on top of the wall to hit it with sledgehammers and tear it down. And then, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, perestroika, and a reunified Germany, the Wall - with it the other relics of the Cold War - receded from my imagination.

It wasn’t until I moved here, and could see the city up close, including the remnants of the wall that remain - that I could begin to understand it in a human context. Of families separated, a historic capital literally torn apart - that the Wall was really a wound, leaving a scar, and in many ways still healing.

As I am writing this on August 12, 2024, just over two years after moving to Berlin - I decided to post some of the misconceptions I had about the Wall as well as the things I didn’t know about it before.

The wall was built 14 years after the division of Berlin

Maybe it was the way that our American history books summarized events at the end of World War II or maybe I just oversimplified things in my mind.

But for more than a decade after the postwar division of Berlin, residents of the different occupation zones could travel between them.

Even after the establishment of the two separate German countries (the communist German Democratic Republic and the democratic Federal Republic of Germany), residents of Berlin could travel between the FRG-controlled West side and the GDR east and vice versa.

But economic differences between the two soon caused tensions. Residents of west Berlin would often shop in east Berlin where groceries were cheaper - many east Berliners held jobs in west Berlin where the wages were higher, but lived in the east where rent was lower.

By 1961, East Germany was experiencing a population shortage as east Germans fled to the west. The GDR had closed its borders outside Berlin 1949, but the looser restrictions within the city led to a near flood of people leaving for West Germany.

In the months before the border was hardened, there were rumors that the East German government had something planned. But as late as June, GDR leader Walter Ubricht stated “nobody has any intention of building a wall.”

But by dawn on August 13, roads crossing the border between east and west Berlin had been torn up, concrete and sections of rubbled were piled up to create barricades. In places, fence posts were driven into the ground and barbed wire was strung between them.

For residents living right on the border, the situation was surreal.

Along Bernauer Straße in central Berlin, authorities bricked up the windows and entrances of the first floors of apartment buildings that opened onto the street - which was in the French-controlled sector of West Berlin, but the buildings themselves with in the Soviet-controlled East.

On August 22, Ida Siekmann became the first person to die trying to escape East Berlin after she jumped from her fourth-story apartment window at 48 Bernauer Straße to the street below.

“Ida Siekmann [had] crossed the border regularly since the border situation required her to enter her building from West Berlin. Moreover, she was likely to have paid regular visits to her sister, who lived just a few blocks away in the western section of the city. When the Communist Party leadership sealed off the entire sector border on August 13, 1961, the situation for Ida Siekmann, who lived alone, changed dramatically. Like hundreds of thousands of Berliners, she was cut off overnight from relatives and acquaintances living in the other part of the city.

…

These measures instilled fear in the residents and, in desperation, many of them jumped from their windows or climbed down a rope to escape to the West. The West Berlin fire department stood on the sidewalk and tried to catch them in their rescue nets to prevent them from getting injured. On August 21, Ida Siekmann watched as the entrance to her building was barricaded shut. Early the next morning she threw her bedding and other belongings out the window of her third floor apartment. Then she jumped. Perhaps she was scared of being discovered. The West Berlin firemen had no chance to catch her in their rescue net. She was badly injured when she hit the sidewalk and died on the way to the nearby Lazarus Hospital – one day before her 59th birthday.”

–Chronik der Mauer (Chronicle of The Wall).

People used the subway tunnels and sewers to escape

In the early days of the Wall, people who wanted out of East Berlin went underground–navigating the U-bahn subway tunnels to the other side. Two U-Bahn lines (U6 and U8) and one commuter S-Bahn line had starting and stopping points in the West, but traveled through the East.

“Just imagine: You’re on your typical morning commute to work when suddenly a warning comes over the loudspeaker: “Last stop in West Berlin!” You then descend slowly into the underground of a foreign country under socialist rule where you see phantom-like armed East German guards on dimly lit platforms peeking back at you through narrow slits in bricked huts. It’s no wonder these eerie stations were soon dubbed as “ghost stations” by West Berliners.”

–Inside the Forgotten Ghost Stations of a Once-Divided Berlin. Emily Wasik. Atlas Obscura, March 10, 2014.

The trains no longer stopped at the stations in East Berlin, but would slow down as the passed through the “ghost stations” and some people would jump on the moving U-Bahn or walk through the tunnels when the trains weren’t running. Eventually, the government stationed guards in the subway stations, put spikes on the platforms, and then bricked up the station entrances.

Deterred from the subway, some tried to swim through the sewers to freedom, until they installed grates inside the tunnels before they went under the west side.

The Wall completely surrounded West Berlin

Berlin was physically located entirely within the GDR, so to keep East German citizens from fleeing to the west through Berlin, the Wall had to surround the other half of the city. When it was finished the Berlin Wall was 168 kilometers (104 miles) long.

The surrounding German federal state of Brandenburg was also East Germany.

Some border towns in Brandenburg were surrounded on three sides and virtually isolated from the rest of the GDR. One exclave of West Berlin, the Wannsee neighborhood of Steinstücken, was completely surrounded by Brandenburg and isolated from West Germany, though it was legally part of West Berlin.

To get a better idea of what this was like, take a look at this interactive map showing the path of the wall. If you’re in Berlin, you can choose to enable location sharing and it will show you how close you would have been to the Wall if it were still standing.

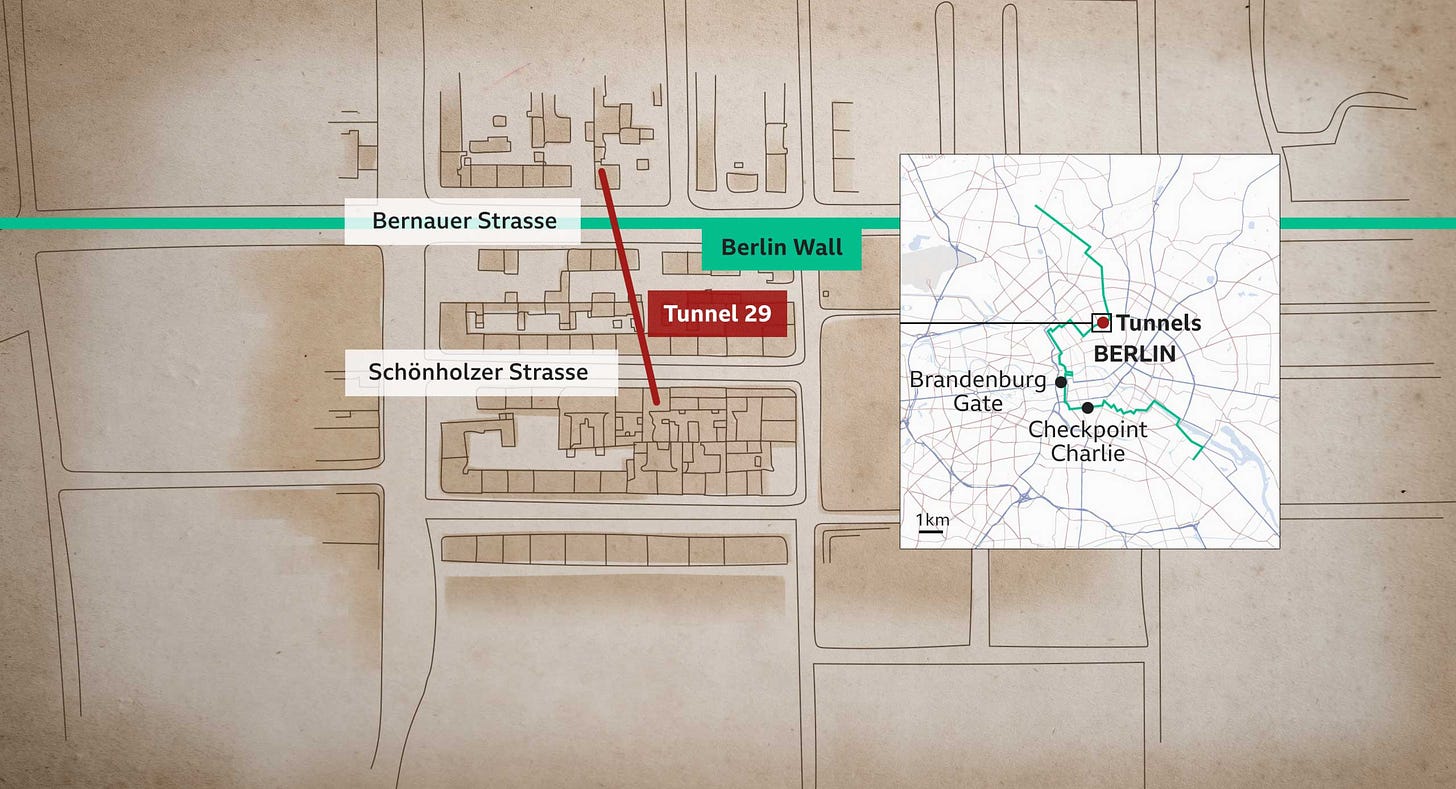

Escape tunnels were dug from West Berlin into the East

During the Wall’s existence, more than 70 escape tunnels were dug underneath to allow people in the east to leave. Only 19 of them were successfully used. Most of them had to be abandoned after their discovery by East German authorities. With one exception, the tunnels were started in West Berlin by volunteer “escape helpers” (fluchthelfer) who risked their lives to plan and construct the tunnels and then guide people through them.

West Berliners could relatively easily obtain visas to visit East Berlin, but east Berliners were almost never allowed to visit the west. The volunteer helpers would visit the east to scout an appropriate location, then return to the west side, plan and dig the tunnel, then return to the east side to help people flee.

The deepest and longest of these was Tunnel 57, through which 57 people were able to successfully escape on October 3 and 4, 1964.

Thirty-five west Berlin volunteers, including Wolfgang Fuchs, future astronaut Reinhard Furrer, and several students at the Freie Universität Berlin helped dig the tunnel from April 1964 until that October. Located 39 feet (12 meters) deep, it stretched 476 feet from the basement of a bakery at 97 Bernauer Straße in West Berlin to a disused outhouse in the courtyard at 55 Strelitzer Straße in East Berlin.

Due to the high water table, the earth was very soft and the tunnels were prone to flooding or collapse if not carefully braced.

Then there was the ever-present threat of discovery. The East German secret police had an extensive network of spies operating in West Berlin, and the border guards used listening devices and seismic monitors to detect underground digging. And, although the escape at Tunnel 57 was successful, what followed exemplified the risks:

“On 4 October around midnight, the second night of fleeing, two Stasi officers in plain clothes presented at the entrance, claiming they wanted to flee, and had another friend they wanted to fetch to come as well. When they returned not with a friend but with border guards, one of the helpers, Christian Zobel, shot at the guards, hitting Egon Schultz on the shoulder. He fell to the ground, and, while trying to get up again, was fatally shot by friendly fire from one of his fellow officers.[1]

Seeking to use the incident for propaganda, the East Berlin press reported on the following day that "West Berlin terrorists" had murdered a border guard. The SED, the GDR's dictatorial ruling communist party, spread this rumor and made a martyr out of Schultz, the victim of a ruthless enemy of the border [Grenzverletzer]. Only after German reunification could the exact events be recreated using the Stasi's records from the time. Zobel wrongly believed that he had fatally shot Schultz right up until his death in the 1980s.”

–Tunnel 57. Wikipedia. Accessed August 12, 2024.

At least 140 people lost their lives

Although the Berlin Wall was purported to be a protective measure meant to prevent the intrusion from the West of "fascist elements conspiring to prevent the will of the people,’ it was always clear that the purpose was to prevent the citizens of East Germany from leaving.

Committing the crime of Republikflucht (“fleeing the Republic”) was punishable by a prison sentence of at least three years. Often, those caught in the act were also charged with espionage and other offenses, which made the sentences longer.

From 1982, border guards were under explicit orders to shoot anyone who encroached on the protected border area without authorization.

One of the most well-known “victims of the wall” was 18-year-old Peter Fechler. On August 17, 1962, Fechler and a friend attempted to escape over the wall. Fechler had almost made it over the outer barrier, but was shot by border guards and fell back into the death strip.

He was left wounded and bleeding feet from the western side and over the next hour bled to death in front of observers on both sides.

Some people who were killed at the wall were not attempting to flee. The Berlin government website dedicated to memorializing the people who died fleeing East Germany notes:

“At the Berlin Wall alone, at least 140 people were killed or died in other ways directly connected to the GDR border regime between 1961 and 1989, including 100 people who were shot, accidentally killed, or killed themselves when they were caught trying to make it over the Wall; 30 people from both East and West who were not trying to flee but were shot or died in an accident; 8 GDR border guards who were killed on duty either by deserters, fellow border guards, a fugitive, someone helping fugitives, or a West Berlin police officer; and at least 251 travelers from East and West who died before, during, or after inspections at checkpoints in Berlin.

Two of these people were 10-year-old Jörg Hartmann and his friend, Lothar Schleusener, 13, who entered the border strip in the district of Treptow just after dark on the night of March 14, 1966.

“It was about 7:15 p.m. when the two boys were noticed by border soldiers that evening near the garden colony "Sorgenfrei." A report stated that the border guards "recognized as silhouettes two people who had passed the interior barrier." When they did not respond to the warning shots, the guards opened fire.

–Chronik der Mauer. Victims of the Wall.

Jörg was killed instantly, but Lothar was brought to the People’s Police Hospital in Mitte where he died later of his injuries.

The deaths were covered up by the East German police who told the families that their children had died separately in accidents. Jörg’s body was cremated and buried before his family was even informed that he had died.

“Lothar Schleusener had been missing for days before his mother was officially informed that he had died from an electric shock in Espenhain near Leipzig. A death certificate from the Leipzig registry office apparently certified this. In private Lothar Schleusener’s parents doubted whether the information provided by the authorities was true. They could not explain how their son had ended up in Leipzig, but because they feared reprisals, they did not dare express their mistrust openly. Lothar Schleusener’s sister said that their mother basically knew that she had been lied to. Her mother knew that western radio had reported that two children were shot at the Wall on the day her son had disappeared. Out of grief and fear she never spoke about the death of her son and asked her daughter not to speak of it or ask any questions.

–Chronik der Mauer. Victims of the Wall.

What really led to the ‘fall’

Though some Americans like to mythologize Ronald Reagan’s 1987 Berlin Wall Speech (“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”) - or the rock concerts by Bruce Springsteen or David Hasselhoff as signaling the beginning of the end, the events that led to the opening of the Berlin border were a result of years of work from inside East Germany.

During the summer of 1989, demonstrations by young people all over the Soviet Union called for greater freedom of expression and freedom to travel, culminating at a large demonstration called the Pan-European Picnic in August on the border with Austria and Hungary.

Leaders there agreed to open the border between the two countries, which allowed East Germans and others from Soviet bloc countries to seek asylum in the West. This led tens of thousands of East Germans to immediately try to go to Hungary - a refugee crisis for both countries.

In response, the leadership of the GDR decided in October to loosen travel restrictions at certain checkpoints, including those between East and West Berlin. The regulations were originally supposed allow East Germans to appy for visas in advance and under conditions that were more permissive than they had been. In early November, just before the new regulations were announced, they were suddenly amended to also allow for immediate emigration at the border.

A mistake in communications led East Berlin party leader Günter Schabowski to announce in a television broadcast on November 9 that the regulations were effective immediately, and then thousands of Berliners began overwhelming the guards at the border checkpoints.

“The surprised and overwhelmed guards made many hectic telephone calls to their superiors about the problem but it became clear that no one among the East German authorities would take personal responsibility for issuing orders to use lethal force. As a result, the vastly outnumbered soldiers had no way to hold back the huge crowd of East German citizens. In face of the growing crowd, the guards finally yielded.”

–Wikipedia. Bornholmer Strasse border crossing. Accessed August 19, 2024.

That’s what I’ve learned so far about the Berlin Wall. Did you learn anything you didn’t know before? What do you think more people should understand about the Wall? Leave a comment and let me know.

More About the Wall

You’ll notice that this week’s update is something of a themed issue.

Reading

TIME. I Was Just a Man Who Sang a Song About Freedom’: 30 Years Later, David Hasselhoff Looks Back on His Surprising Role in the Fall of the Berlin Wall by Olivia B. Waxman, November 19, 2017.

Zeitgeist. Berlin’s Cold War of Rock by Katja Hoyer.

Watching

‘Berlin’s Strangest Border’ with YouTuber Matthias Schwarzer. (In German, but there are English subtitles.)

Listening

Tunnel 29 - a podcast from BBC Radio is the history of one of the escape tunnels dug under the Berlin Wall. (h/t Zeitsprung via Handpicked Berlin).

Very Informative- I did not know most of the things contained in this article-it is so sad so many lost their lives trying to escape.

One other thing-David Hasselhoff had something to do with it?