Should You Move to Germany?

Dispelling some myths--pro and con--and offering some tips about immigrating here

I’ve had this post kicking around in the drafts folder for a while, a more localized take on this one by Brent Hartinger over at Brent and Michael are Going Places.

As the results of the U.S. election have prompted an uptick in people expressing interest in emigrating, I think now is a good time to publish it.

For now, I’ll leave aside the question of can you move to Germany. Do you have or are you able to get a work or study visa, have the financial means, etc. Those are topics for future posts. (Because it is both harder than many think, but easier than some others have said.)

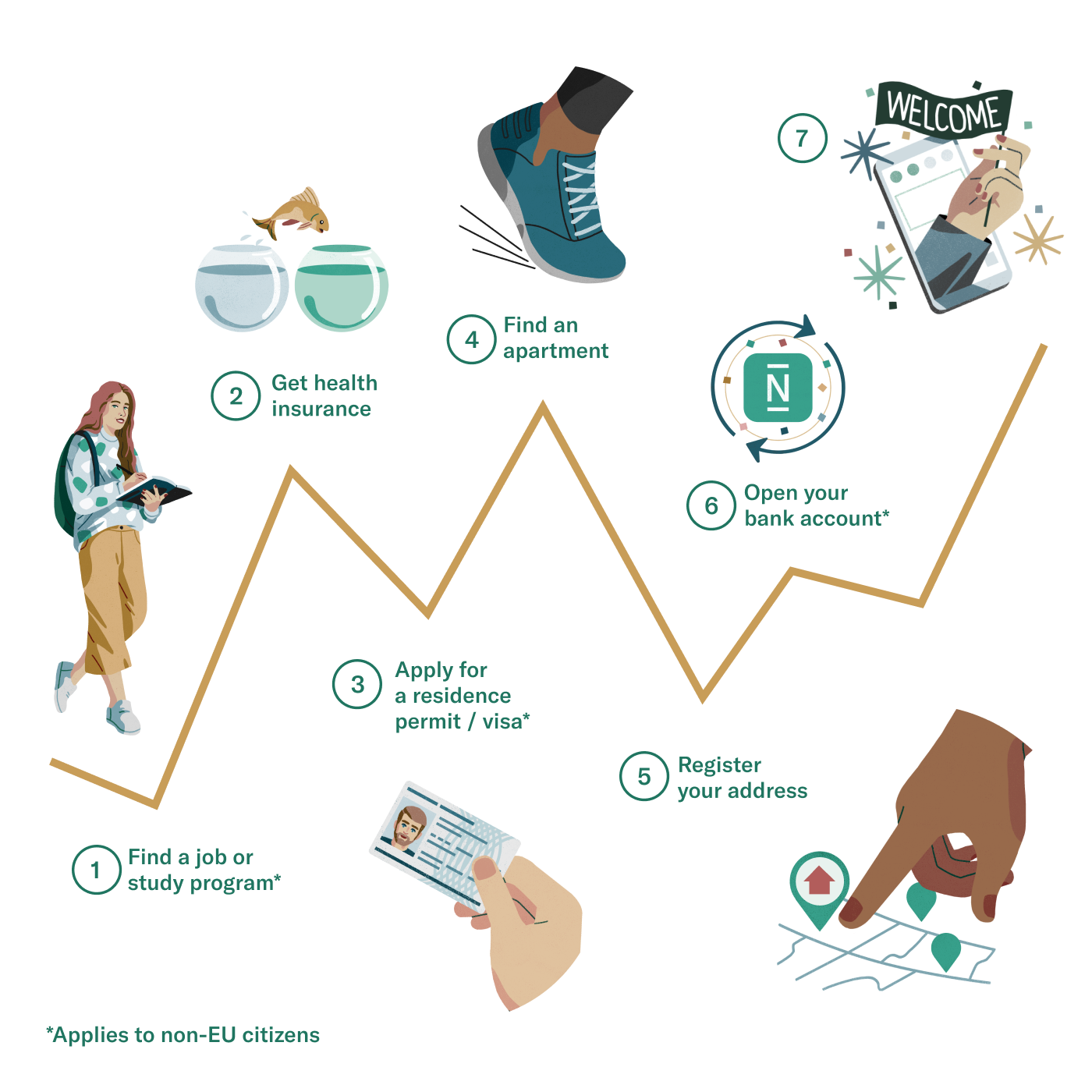

And, other people have written better articles in the ‘how to do it’ arena. Here’s a start:

I’m focusing on how to know if you really want to move here. Many people understand the reasons they want to leave the United States—but they spend too little time (in my experience) researching what it’s like to live somewhere else.

Germany is not just the U.S. but with affordable healthcare, lower car dependency, and sane gun control. It does have those things. It also has a different language, different governmental structure and education systems, and different culture, laws and customs.

Below are some of the things I think many people looking to move to Germany don’t know or don’t know enough about.

No digital nomads

I know I said that this wasn’t going to be a ‘can you move’ article. But, this is a common misconception that I see posted over and and over on social media, Reddit, etc. Your work is 100 percent remote, so you can work ‘from anywhere.’

Well, not from Germany—unless it’s from your temporary vacation to Germany.

There is no digital nomad visa here.

It might be possible, if your current company is willing to agree to comply with the tax withholding and work regulations of the Federal Republic of Germany in order for you to work here, but most companies are not going to go to that amount of effort for individual employees.

Even if you are able to obtain German citizenship through familial descent and don’t need a visa to move here—if you need to work to support yourself, you need a German employer, or German clients if you are self-employed or a freelancer.1

If you work for a German or multinational company with offices in Germany, you can pursue a transfer of your employment to the German division (essentially what my husband did). But you won’t be able to do your U.S. based remote position from here.

This is due to the different tax and labor laws in the two countries.

If you live in Germany, you have to pay German income tax regardless of where the money was earned. (Also, if you’re a U.S. citizen, you still have to *file* your U.S. taxes every year, although you will get a credit for most of the tax already paid on your income in Germany.)

Getting and keeping a job and visa

The international media is full of articles about the labor shortage in Germany and efforts by the governing coalition to attract foreign skilled workers.

There is the Chancenkarte, the EU Blue Card, and other programs established by the federal government to attract needed talent. I’ve covered the proposed tax breaks for new workers in a previous post.

But it’s important to remember that Germany (like the U.S.) is focused on making sure that it has the workers its companies need—not on making it a smooth transition for foreign workers to live here.

In the three years we have lived here, I’ve met many people who unexpectedly found themselves unemployed or under-employed after moving for what turned out to be a bad opportunity.

For example, I know two different people who moved their young families to Berlin after receiving a temporary employment contract that they hoped would lead to permanent employment. It didn’t, and they ended up moving back to the States after not being able to find similar positions in Germany.

I know others who accepted an offer for what turned out to be a salary too low to even qualify for the appropriate work visa. They found out the onus is on the worker to go back and negotiate for a higher salary, look for new position, or quit and leave the country.

Look carefully before you leap.

Salaries are lower, taxes are higher

Salaries are typically lower all across the European Union than they are in the United States. And the taxes are higher. Universal health coverage, tuition-free higher education, and a large social safety net are expensive, after all.

I’m of the opinion than you get a lot in return for those higher taxes, but they can put you in a crunch.

My husband took a significant salary cut to accept a permanent work contract at the German subsidiary of his previous employer, our taxes almost doubled, our housing costs are more expensive, and we pay private school tuition for our oldest child.

We are fortunate to be able to do this. But we had to dip into our savings to both pay for moving costs and some of our living costs the first year. And the private school tuition is being covered by the profits from selling our house in the States.

In general, the days of the cushy expat relocation package—where employers absorb the costs of moving and housing for their foreign workers— are gone. Maybe there are some high-level multinational company officers who get them—and then usually if it is a temporary assignment.

Learning the language

German is not an easy language. It’s probably easier for native English speakers than for anyone—but the U.S. State Department still considers it a Category II (about a medium level of difficulty) for its diplomats to learn.

Also, there’s a big difference between being able to navigate the grocery store and restaurants in another language and, say, having to go to the doctor, give a business presentation, or participate in a parent-teacher conference in it.

For the record, after three years of sustained effort, I feel reasonably confident in most situations—talking to my son’s teacher, reading and responding to official correspondence, going to the doctor. But I am still taking a translator the next time I have to visit the Bürgeramt (see below).

I don’t have an official certificate. My goal is to pass the B1 test this year, and apply for permanent residency, and then go for B2/C1. Even then, I don’t know when I will feel comfortable saying I am fluent in German.

Laws, regulations, oh my!

There’s a reason why so many comedy sketches send up German regulations. There are a lot of them.

I wrote before about the specific rules for properly sorting the trash. Here, recycling is not an optional exercise for the eco-friendly, but both a legal and moral obligation.

There are many other things that are either allowed or tolerated in the U.S. that will here net you a hefty fine - even in supposedly anything-goes Berlin.

Bureaucracy

The best way I can succinctly describe German bureaucracy is that one needs to get very comfortable with waitlists, waiting times, and, sometimes, living in limbo.

Almost every aspect of your life will entail getting some type of written government authorization for something—some times several types—which necessitates getting an appointment with a government office, which necessitates making the appointment far in advance, then waiting for the appointment to take place.

In many cases, you need a signed authorization from one government office to apply for something else at a different government office. For example, to apply to the Finanzamt (tax office) for Kindergeld (the payments the German government gives to families with children), you have to submit an application that includes a statement of residence from your local Bürgeramt (citizens’ office). This statement is completely different from the statement of residence you got when you registered your residence at the citizens office, even though that statement also listed the names and ages of all family members, just like the second statement does. It has to be that. specific. form.

And you will wait months to get both of those appointments.

At some point, some essential document will expire or be about to expire and there will be no available appointments at the relevant ‘Amt’ office in time to prevent the document from expiring.

You will then get on the waiting list for the next available appointment, keeping all the documentation of your attempts to get said appointment, and then, the all-important appointment confirmation in case someone needs to see your now-expired document in the meantime.

This is life now.

Speaking of which, I need to go remind my husband to check on an application …

Owning and driving cars

For us, one of the main attractions of Germany was the lack of car dependency. We wanted to live somewhere we would not need a car to get around. We are particularly spoiled with great public transit in Berlin, as well as decent cycling infrastructure. We are glad to be car-free.

And that’s good.

Because having and owning a car in Germany is expensive. Unless you come from a state with license reciprocity (and we did not), it costs between €2,000 - €4,000 to get a German driver’s license. Gasoline is also between two and four times more expensive in Europe than in the United States.

Currently, a gallon of regular gasoline is selling for $3.085. In Germany, the price is € 1.691 per liter, which is about €6.40 ($6.83USD) per gallon.

There are also requirements (and costs) for registration and insurance, but these are on average lower than in the States.

In Berlin, if you live inside the Ring, you need a resident’s parking permit to park on public streets—farther out street parking is free. The parking permit is a little over 20 euros for two years, which is a serious bargain compared to other large cities.

And, while there are parking spaces, parking decks, and some parking lots—there are not the massive acres of parking lots that you see in North America. Even in the outer areas of Berlin, which less dense and more car-friendly (nowhere, in my experience, is truly ‘car dependent’ here), the number and size of parking lots is smaller. Finding parking is a hassle.

Making friends, building a life

Surveys of immigrants to Germany indicate that difficulty making friends or feeling integrated in society are the top reasons many cite when asked reasons for deciding to leave the country.

My informal observations are that this is due to a combination of cultural differences and expectations. I think Germans—in general—do not quickly form new friendships, but their friendships tend to be longer lasting. They don’t have as many friendly acquaintances/or transient friendships the way that people do in other places.

They also don’t have lives and friendships centered on their work life. I think many people are friendly with their coworkers, but don’t socialize, or expect to, with coworkers outside of work.

In the U.S.—again, in general—I think people are much more likely to have a lot of their social lives and identities centered on their jobs or profession. And it’s hard to make the transition.

But, Germans are very into their hobbies and social groups formed around leisure activities.2 No matter what hobby, game, or special interest you have, there’s probably a local verein (association) for that.

Volunteering is also a good way to meet people and interact socially. And there are tons of opportunities for that in Berlin, a well.

We have had good luck meeting people with shared hobbies and activities, but it takes some effort to find these groups. And, of course, they are mostly in German.

Final verdict

For us, the benefits of being able to immigrate to Germany have been worth the sacrifices and challenges.

When we moved here, I was mostly worried about my kids. I knew we would be OK, but my husband and I were already middle-aged and established. I was worried I might be too old to learn German, but knew I’d get by.

But our kids would be in a strange place, learning a new language, and having to make new friends, at an age when that’s already difficult no matter where you are.

But they have both told us they are happier living here than they were in the States, though they still miss their friends and family there.

For us, the decision to emigrate was not a sudden one—and it was not because of just one societal issue or one bad election. We knew there would be tradeoffs. You get certain things, but give up others.

If you’re considering leaving the U.S., obviously I understand, but make sure you look carefully at where you want to go, and what the tradeoffs will be. Only you can decide if they are worth it.

I am a dependent to the holder of a EU Blue Card and legally allowed to work and freelance for international and German clients.

Again, this is my observation, feel free to share your perspective in the comments.

Brit here, married to a German, kids all born and bred in UK, but have dual citizenship, so, post-Brexit, decided to up sticks and get a German (EU) passport for me, the useless non-EU one. And because we want to live one day in a European country where the sun shines more than it does in Manchester…not too difficult an ask.

And, though I’ve been coming to Germany several times a year for the past 30-odd years, living here in Berlin has still presented me with a few small shocks I wasn’t expecting.

1. The bureaucracy.

2. The bureaucracy.

3. The bureaucracy…I’ll stop there on this one…for I could go on and on and on…

4. The cultural differences my wife, who’s lived in the UK for over 30 years, describes as ‘a cultural difference, but I call rudeness. Just not like home, where we apologise when someone steps on our foot…ha-ha. No chance of anyone here apologising for that at all!

5. The general sense of impatience all Germans seem to have about and with everything. I read somewhere that Germans don’t drive to be safe, they drive to prove they are right, and that’s about as much of a nutshell when it comes to describing them.

6. Their complete lack of tact. Nonexistent here, so if you’re harbouring a spade, be prepared to get called out on it here!

But, and this is a very big but, I think life here is better than it is Manchester, or anywhere else in the UK, so Incan only imagine how much better it is, in theory, than it is in the US.

But, and this is a bigger but than the last one, the language is a bugger. Much harder than I anticipated, and I’m resigned to not being able to express myself in German as well as I do in English, which was, believe it or not, a delusion I harboured for quite a while. But, with hard work and application, I know I’ll get close to an approximation of someone who speaks the lingo well. I think…

And, finally, I love living in Berlin. Not Germany, for Berlin most definitely is not Germany, but Berlin. It is one of the world’s great cities, and should be on anybody’s list as a must-see place, and, if you can, try living here, even if only for a while.

Great post, Cathi!

We went through all of this to work at my husband‘s headquarters in Kassel, only for my children and him to not like it and want to come home. I could have stayed forever and every time we go to the doctor or I go grocery shopping I let him know. When we go to Michigan instead of Paris, I let him know. I didn’t even mind everything being closed on Sunday.