The “exhibition trench” of the Berlin Topography of Terror Documentation Center runs alongside Niederkirchnerstraße in Kreuzberg just below the street level. It contains one of the center’s standing exhibits, “Berlin 1933-1945—Between Propaganda and Terror.”

The trench is actually a path adjoining the excavated foundation of the former Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office) site of the headquarters of both the Gestapo and the Nazi SS, as well as a notorious basement prison.

Tracing the history of National Socialist politics in Berlin, the exhibit documents how they used propaganda and fear to go from being an banned extremist group during the last years of the Weimar Republic, to seizing control of the government, to then implementing militaristic control over almost all aspects of German life.

People who opposed the Third Reich’s vision for its unified “people’s community” risked finding themselves in an interrogation cell at the foreboding headquarters that once occupied this site.

And, yet, as one small part of the exhibit describes—some Berliners did.

The Familie Foß

In November of 1942, the Foß family —Hans, his wife, Margot, and teenage sons Werner and Harry—received a notice for deportation at their Charlottenburg apartment.

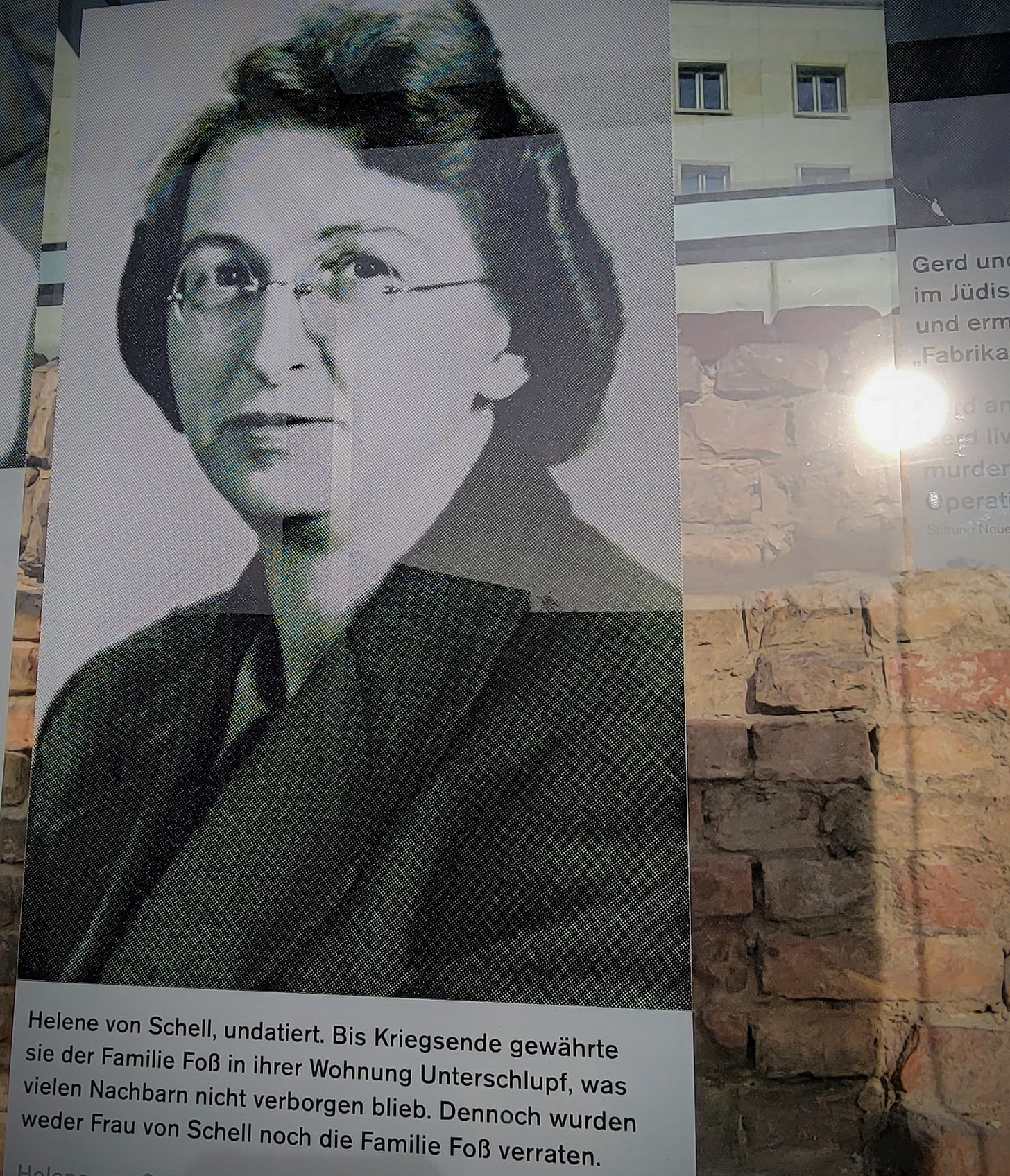

A family friend, Helene von Schell, was visiting them at the time and told them, “You’re not going along with that. You’re coming home with me,” according to an account Werner later gave to a reporter.

Schell, a 39-year-old secretary who lived alone in a one-room apartment at 6 Waldstrasse in Moabit, kept the family hidden there for two years, sleeping in her kitchen while the family occupied the living room.

As was common in apartment buildings at the time, there was only a shared bathroom for the whole floor. In the evenings, when all of the building tenants were home, they had to avoid using it for fear of discovery. The immediate neighbor was a Nazi Party member who, fortunately, worked until late in the evenings. His wife, who knew of von Schell’s guests, didn’t tell her husband and also helped the family obtain food.

Because they did not have identity papers—not even forged ones—the family could not get food rations, and Helene’s single rations did not go far. A different neighbor couple also knew about the family and shared their bread ration.

Other family friends who owned a coal business in Wedding employed the father, Hans, to work in the shop and do coal deliveries. Sons, Harry and Werner, worked as messengers and Margot found piece work repairing womens’ hats.

People who knew Helene von Schell later attributed her decision to her strong Christian faith. I have to wonder if she—a single woman, living alone— also felt stigmatized as inferior in the Nazi-idealized “people’s community,” with its fetishization of the nuclear family and German motherhood.

Independent of the strong sympathy that Helene von Schell had for my father, she was also courageous in her whole being. She had a strong sense of justice coupled with personal fearlessness.

-Harry Foß, in his statement to Yad Vashem assessing the motives of the protectors.

The Nazis encouraged “Aryan” parents to have as many children as possible, giving such couples money when they married and loans to buy homes—with a portion of the loan forgiven for each child produced.

But Helene von Schell had a different people’s community.

All four of the Foß family survived until the Allies took control of Berlin. The parents remained living in the apartment house in Moabit after liberation, with Margot caring for Helene during her last illness.

Helene von Schell died there in Berlin in 1956. Hans died in 1969, and Margot Foß lived in the house until she moved to a retirement home in 1980. She was the last tenant there to have lived at Waldstrasse 6 before the war.

In February 2000, Helene von Schell was posthumously recognized by Yad Vashem - World Holocaust Remembrance Center as one of the Righteous Among the Nations, for risking her life for her friends.

Hans Rosenthal’s Garden

While the Foß family navigated their secret live in Moabit, over in the east, future radio broadcaster Hans Rosenthal was alone and desperate.

His parents had died, and his brother, Gert, had been deported from the Jewish orphanage they had been sent to. The teenage Hans was only alive because he had earlier been sent away to a camp for “insubordinate youth” and then to work as forced labor.

In 1943, he came back to Berlin to seek help from his non-Jewish grandmother, Anna. She was afraid he would be too easily found with her, so she asked a friend, Ida Jauch, for help.

By 1943, Ida had begun living and running a small textile businesses from her allotment garden at Dreieinigkeit Kolonie in Lichtenberg. Jauch hid Hans in a tiny shed in a corner of her allotment. He could only come out at night, when air raid sirens were sounding.

Ida shared her food rations with him and his grandmother, Anna, also brought food when she could.

In September of 1944, Ida Jauch died suddenly. And Hans had to risk everything to ask a garden neighbor, Maria Schönebeck, for help. Schönebeck, whose husband and son were away serving in the German army and navy, agreed to take him in. She also hid him in the garden colony and brought him food, later recruiting others to provide food, as well.

Hans survived in hiding until the area was liberated by the Russian Army in 1945. He continued to live in Berlin, first in the east and later moving to West Berlin, where he became one of the most famous broadcasters and radio hosts of the postwar years.

In his biography, Zwei Leben in Deutschland (Two Lives in Germany) he writes about his experiences during the Holocaust and the women who helped him.

In 2011, both Ida and Maria were posthumously named as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. They are among the only 569 German people to have been so recognized.

“Bystanders were the rule, rescuers were the exception. However difficult and frightening, the fact that some found the courage to become rescuers demonstrates that some freedom of choice existed, and that saving Jews was not beyond the capacity of ordinary people throughout occupied Europe. The Righteous Among the Nations teach us that every person can make a difference.”

—Yad Vashem. Who Are the Righteous Among Nations?

Quiet heroes

The above are just two instances of non-Jews helping Jewish people during the Holocaust. The women mentioned—Helene von Schell, Ida Jauch, and Maria Schönebeck—were not the only Berliners who resisted the Nazis to help Jewish people. And they were not the only women.

You can find more stories like these at the website for the Silent Heroes Memorial Center (Gedenkstätte Stille Helden), and this Wikipedia list of the Germans who have been named Righteous Among the Nations.

People who sheltered Jewish people and others facing Nazi persecution faced serious punishment—even death—if they were caught, though punishments for those living in Berlin and other parts of western Europe were usually not as severe as those faced by resisters in occupied eastern Europe.

“The price that rescuers had to pay for their action differed from one country to another,” explains the website for Yad Vashem, in its article, “Who Are the Righteous Among the Nations?” “In Eastern Europe, the Germans executed not only the people who sheltered Jews, but their entire family as well. … Generally speaking punishment was less severe in Western Europe, although there too the consequences could be formidable and some of the Righteous Among the Nations were incarcerated in camps and killed. Moreover, seeing the brutal treatment of the Jews and the determination on the part of the perpetrators to hunt down every single Jew, people must have feared that they would suffer greatly if they attempted to help the persecuted.”

Still, the number of people who helped was a small minority compared to the number of Germans who refused to help or even collaborated in and benefitted from the persecution and murder of Jews and others.

When the National Socialists came to power, there were 160,000 Jewish people living in Berlin. By 1941, roughly 90,000 had left Germany due to Nazi persecution. Between 1940 and the end of the war in 1945, around 50,000 Berlin Jews were deported to concentration and extermination camps. And around 7,000 Jewish people attempted to survive “underground” and go into hiding in Berlin when the deportations started. Of that number, only 1,400 survived.

“Aid and rescues were an exception,” notes the information page for the Silent Heroes Memorial. “The permanent exhibition shows that help was in fact possible, however, and that it did happen in many European countries. The extent, success, and conditions of that help varied in the different countries of Europe, while there were diverse motives for helping.”

I fear that many times we envision the term “resistance” as only the grand Hollywood archetype: The good guys who triumph over the bad. The plucky band of warriors that overthrows a dictatorship, a corrupt government or ends evil persecution.

None of these women were able to do that. They did not overthrow the Nazi regime—or even attempt to. They were not able to save all of the Jews. In some instances, people were caught, and the rescue failed.

Until relatively recently, their actions remained secret, except to those that they helped and, sometimes, their family members.

But they were still able to save lives to retain their humanity and compassion and dignity in the face of overwhelming odds.

As the Yad Vaschem memorial states, the example that they set shows that resistance is possible and—even if it is small—it is important.

“They were ordinary human beings, and it is precisely their humanity that touches us and should serve as a model. The Righteous are Christians from all denominations and churches, Muslims and agnostics; men and women of all ages; they come from all walks of life; highly educated people as well as illiterate peasants; public figures as well as people from society's margins; city dwellers and farmers from the remotest corners of Europe; university professors, teachers, physicians, clergy, nuns, diplomats, simple workers, servants, resistance fighters, policemen, peasants, fishermen, a zoo director, a circus owner, and many more.

…

The Righteous Among the Nations teach us that every person can make a difference.”

Sources for this article

Topography of Terror. Berlin 1933-1945: Between Propaganda and Terror.

Yad Vashem. Righteous Among the Nations - von Schell, Helene.

Antifaschistinnen aus Anstand. Helene von Schell, Secretary.

Moabit Online. Versteckt in Moabit - Stille Helden.

Gedenkstätte Stille Helden. Ida Jauch.

Gedenkstätte Stille Helden. Maria Schönebeck.

Gedenkstätte Stille Helden. Hans Rosenthal.

Frauen im Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus. Elizabeth Gloeden née Kuznitzky.

Museum Blindenwerkstatt Otto Weidt. Jews in Berlin 1933-1945.

Yad Vashem. Who Are the Righteous Among Nations?

More About Jews in Hiding in Berlin during National Socialism

Almost 7,000 Jews went into hiding in Berlin in the last years of National Socialism. They were known as “untergetauchten” (submerged) or even as “U-boats,” they led secret, and sometimes double, lives in Berlin. Here are links to more of their stories.

Philip Oltermann. “Submerged: The Jewish woman who hid from Nazis in Berlin.” The Guardian. March 16, 2014.

Renee Ghert-Sand. “How a young Jewish man with a talent for forgery hid in plain sight in World War II Berlin.” Times of Israel. March 15, 2023.

BBC. “Three women who were part of a quiet resistance against the Nazis in Berlin.” January 26, 2020.

Now that's courage.